My gateway to period dramas starring white girls was probably Anne of Green Gables, a Canadian classic from 1908 about an irrepressible orphan who dreams of being a writer. I consumed the books and the 1980s Emmy-winning TV series as a kid, and by middle school, I was reading Jane Austen’s Emma. Then came 1995, a legendary year for Austen fans. Clueless, BBC’s Pride and Prejudice, and Ang Lee’s Sense and Sensibility with Emma Thompson and Kate Winslet were all released, followed by Emma with Gwnyneth Paltrow in 1996. This Black biracial teen was hooked for life.

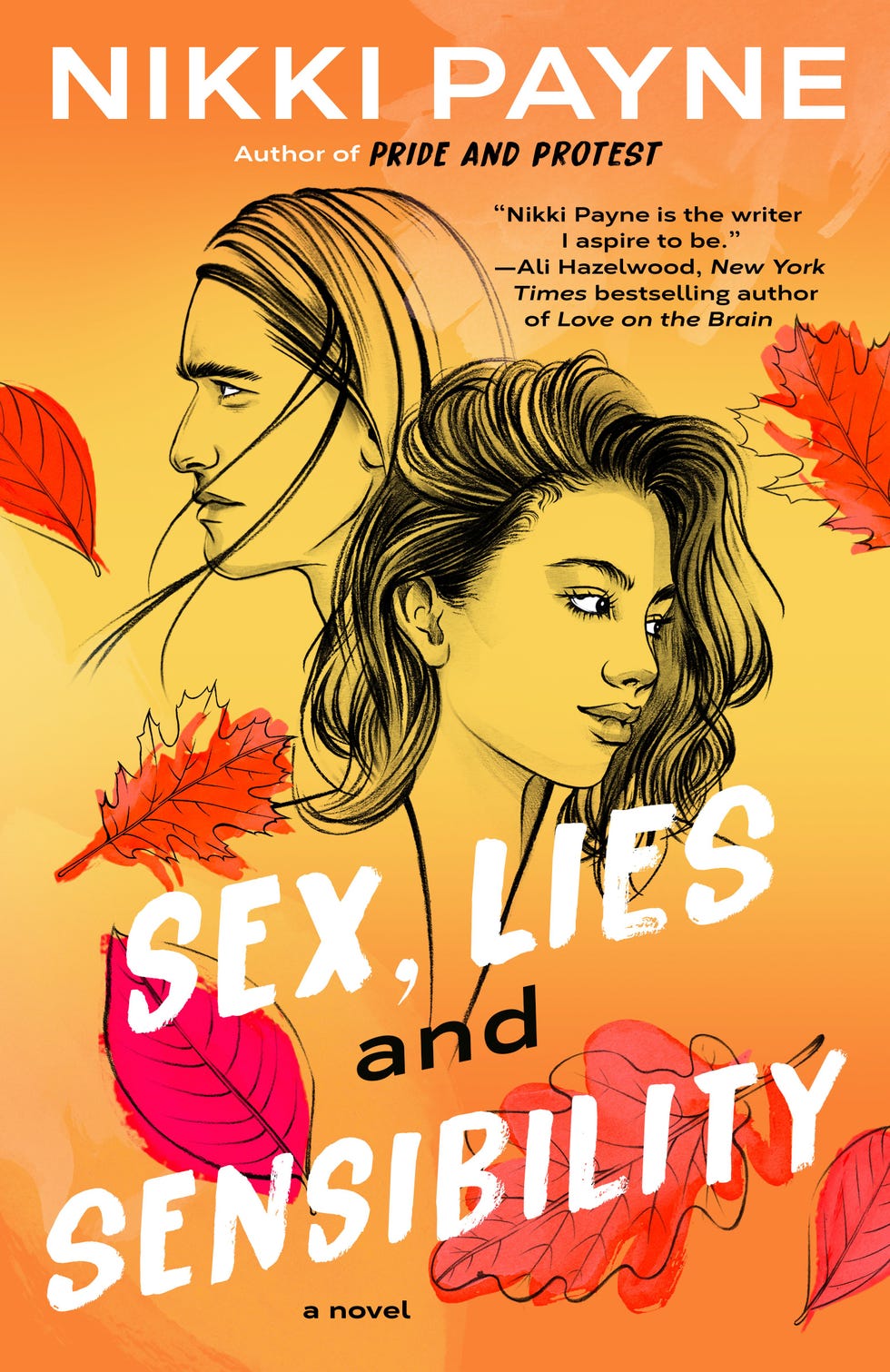

Diverse fans of Austen have been faring well lately—Sanditon on PBS and Persuasion on Netflix featured diverse casts, and Bridgerton brought a similarly vibrant ‘ton to life under Queen Charlotte. (Not Austen, but still welcome.) In the fiction space, we’ve seen a welcome spate of modernized takes from authors like Sonali Dev, Uzma Jalaluddin, and Nikki Payne, whose latest Austen adaptation, Sex, Lies and Sensibility, came out last month. Payne was also impacted by the Austen heyday. “I don’t know how anybody came out of 1995 OK,” she says.

Jane Austen lived during Regency era England in the late 18th and early 19th century. Sense and Sensibility is her first novel, published in 1811. It’s about the lives and loves of the Dashwood sisters—serious, modest Elinor and the passionate, nature-loving Marianne—who are thrown out of their life of luxury into one of lesser means when their father dies without planning any protection or income for them, leaving them homeless. They’re taken in by a relative, and romantic entanglements and misunderstandings ensue.

Like the Dashwood sisters, Jane and her sisters were left homeless due to the actions of her father. He was a reverend from old money, but her family wasn’t wealthy. In Jane Austen, the Secret Radical, author Helena Kelly explains this unfortunate connection. Austen’s parents “hardly seemed to consider their daughters,” she writes. “Jane was penniless. Her father may have loved her, but at his death he left her nothing at all, and even before he died, he’d made her homeless.” Austen and her sisters were left to the mercy of their brother Edward. Neither of them had dowries. “It took Edward four and a half years to get around to providing his widowed mother and his sisters with a home,” writes Kelly. I can’t help but wonder if Austen’s first novel is a rebuttal to this treatment, and if it meant more to her for that reason.

Sense and Sensibility is a favorite of Toni Judkins, SVP of Programming, Mahogany and Executive Producer of the Hallmark Channel’s lush new adaptation, which premiered on February 24 and airs again on March 9. The production includes a mostly Black cast with Deborah Ayorinde as Elinor, Bethany Antonia as Marianne, Akil Largie as the steady Colonel Brandon, and Victor Hugo as Willoughby, among many others. Elinor’s love interest, Edward Ferrars, is played by Canadian actor Dan Jeannotte, who is white and a face Hallmark fans will recognize. “I thought it would be interesting to pair a Hallmark favorite while introducing a new face to our audience,” says Judkins. “By casting Elinor and Edward as interracial love interests, we can challenge preconceived notions of how this classic tale should be told.”

Austen’s classic status makes it ideal for reimagining with a diverse lens. Payne’s novel echoes this with an interracial romance at its heart. “Jane’s work is pre-stamped in the white imagination,” she says. “Telling these stories of color on this template does amazing Trojan-horse work where people can say, ‘This is a safe and familiar story,’ and then they open it up and it’s, ‘Gotcha, it’s a Black story!’” Marriage, home, money, passion, familial responsibility—these themes are ageless and faceless and it’s why Austen endures. “She writes about women whose backs are against the wall, who have no social safety net,” says Payne. “And at this one moment, their decision about marriage is when they have the most agency in their lives.”

Sex, Lies and Sensibility, is about the Dash sisters, tightly wound Shenora “Nora” Dash and her Shakespeare-loving sister Maryanne, a.k.a. “Yanne.” When their wealthy CEO father dies, they discover that they’re his secret family and are cut off, sent to the rural coast of Maine with an impossible task. They must renovate the old Barton Cottage into a profitable inn in one year, or find themselves homeless. Nora makes an instant connection with sexy, conflicted Bear Freeman, who is Abenaki, part of the Wabanaki Confederation in Maine. He knows the land, running a flailing business showing tourists the area and Native handicrafts. He offers to help with the renovation in exchange for using the inn as a tour stop, and they become business partners.

This Sense and Sensibility has some heart-accelerating sex—as the title implies—and yes, hurtful lies as well. But the emotional connection between Nora and Bear draws you in, as well as the deeply-researched education in Abenaki culture and the Black experience in places where they’re racially isolated. Payne visited Maine and spoke to folks on both sides to hear their personal stories over months of research. She wanted to draw attention to the connections between Native people and African Americans. “What came out was this concurrence in both cultures, from experiencing the highest rates of over-policing to what it means to sit at someone’s table and have them touch your braids up,” she says. “These are things I didn’t know before.”

Hallmark’s story is more faithful to the original, and the team worked diligently on the details, hiring consulting producer and author Vanessa Riley as a historical consultant. “Think of her like a Regency Siri,” says creative producer Tia A. Smith. Riley is expert in all the formalities, manners, and minutiae of the era, providing facts and dropping knowledge. “About 15,000 to 20,000 free Black people lived in London during the time of Jane Austen, some of whom were moving into the middle class,” she says. “You will find servants, but you’ll also find people running schools and businesses.”

Mahogany films launched in 2021, and when Judkins first shared her vision for the imprint, she included a Black production of Sense and Sensibility in her deck. You can see her dream in the details: They shot 97 scenes in 15 days on location in Bulgaria and Ireland, says Smith, with long days and a tight-knit team. From the gorgeous and historically-accurate Spencer jackets, Empire gowns and hats in rich colors, trims and fabrics, to all the layers hidden in the background, you’d be surprised how deep the details run. The artwork in the home includes portraits of the first Duke of Florence, Alessandro de’Medici, whose mother was a Black servant, as well as references to the Haitian Revolution and more.

Costume designer Kara Saun and a European tailoring team of just four people made 68 custom pieces in 20 days, often sewing late into the night, communicating by translation apps on their phones. Even the hair was fact-checked. Hair designer Kim Kimble took cues from Riley, creating custom wigs incorporating braids and perfectly curled micro-bangs, which I cannot help but see as baby hair laid the Regency way. All of these tiny specifics made me smile.

I will never get tired of seeing period dramas featuring people of color. Kid me would’ve been delighted at the opportunity to see diversity represented in this way. I can only hope for what’s next: even more original period dramas, featuring different eras, countries, and cultures. More modern mash-ups of classic tales, more history featuring voices still struggling to be seen. From the Bridgerton universe to bestsellers and book club picks, the audience is there.

Everyone I spoke with for this piece was passionate about two things: how Austen’s observations about women, love, and power still resonate 214 years later, and how they welcome new audiences to interact with her work via theirs. “Reading is an endeavor in empathy,” Payne says. “It’s a win for people to find their way to Black stories through a story they already love.”