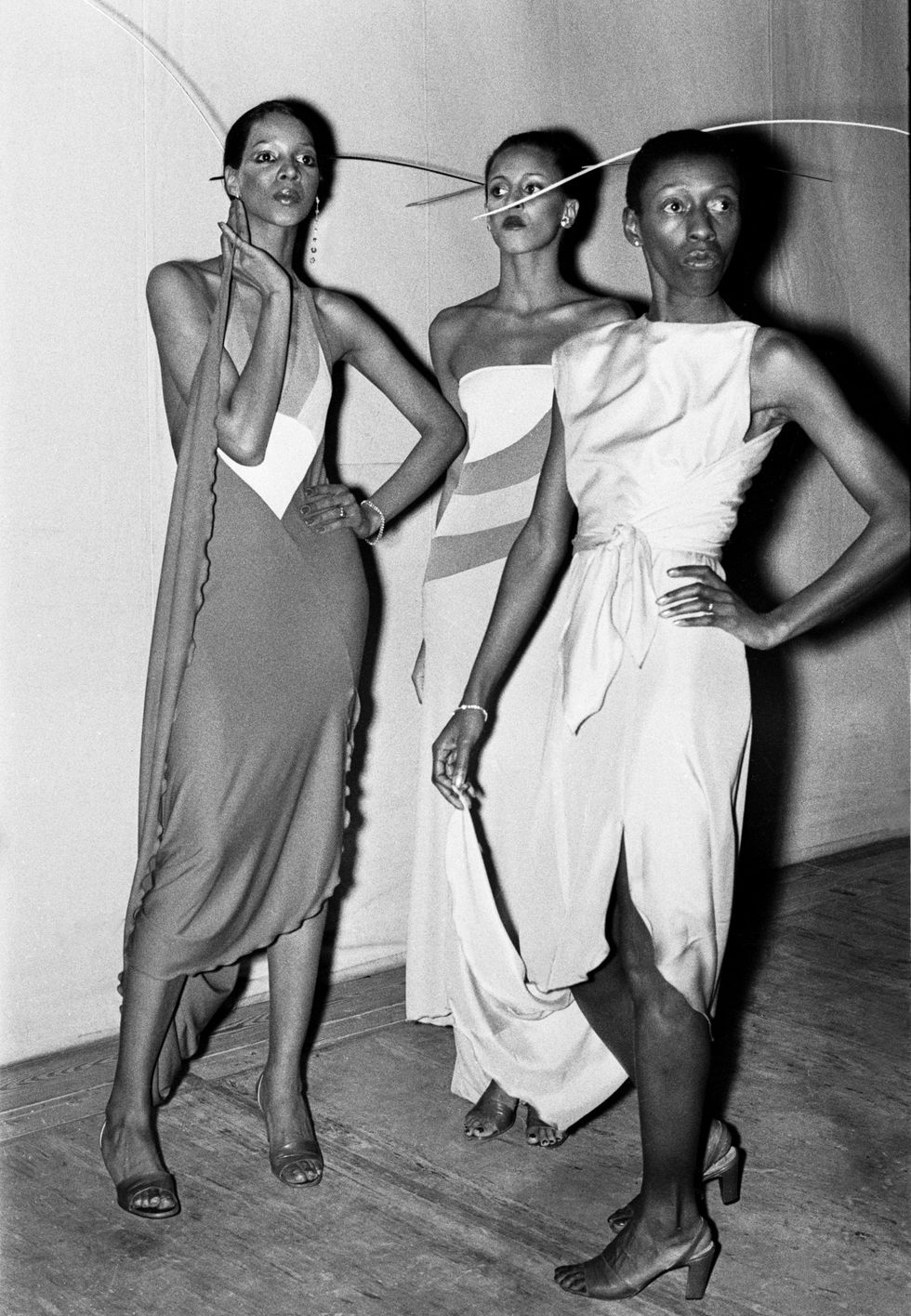

Bethann Hardison is a woman who has lived many lives. She’s a former model, founder of Bethann Management, co-founder of Black Girls Coalition, activist, and now co-director and subject of the documentary Invisible Beauty. Helmed with French director Frédéric Tcheng (Dior & I, Halston), it’s a retrospective of Hardison’s life, covering a lot of ground such as her formative years growing up in Brooklyn, working in the New York City garment district, breaking boundaries as a Black model who defied eurocentric beauty standards, walking in the iconic 1973 Battle of Versailles fashion show, starting her namesake modeling agency, and of course her advocacy for Black models in the industry. But who is the real Bethann Hardison? The documentary answers this question by showing us her milestones and successes rooted in the context of her private life.

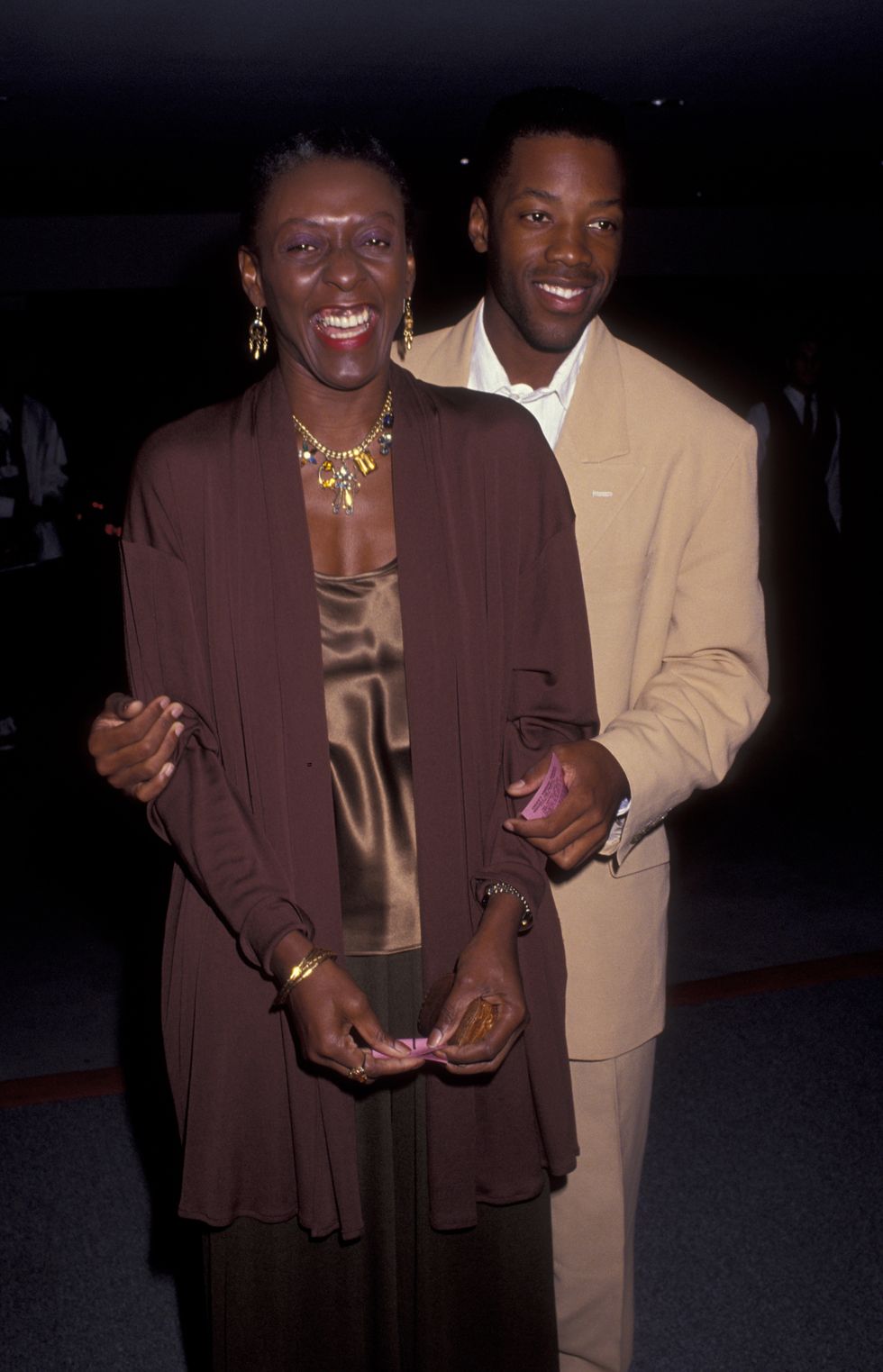

One of my biggest takeaways from the film is Hardison’s role as mother in the literal and colloquial sense. She has a son, actor Kadeem Hardison, but also acts as a protective maternal figure to younger models in the industry. She maneuvers through life purposefully and practically, never missing an opportunity to educate you in a way that is both loving and direct as any good mother would. Modest, but aware of her power, she describes her activism as something was called to do. She feels a “sense of responsibility” toward the people who depend on her to make her voice heard.

Here, Hardison speaks to ELLE.com about how Invisible Beauty came to be, her activism, her role as mother, and her forthcoming book.

More From ELLE

I’m so excited for Invisible Beauty to be widely released. I watched it, of course I loved it. Can you talk a little bit about this chapter of your life as a documentarian and how this film came to be?

This film came to be as I was working on another film that was also titled Invisible Beauty. It was going to be an exposé, I would say, of what was happening in the industry at the time because the model of color had been disappearing, disappearing, disappearing.

Eventually people started saying to me, “You know, yeah, that’s a great idea, but somebody needs to do a story or a film on you.” That wasn’t my idea, nor was it my interest. Eventually the director that I was working with previously and I separated. And then I was on my own with this idea that the film would be about me to help change it, and make sure that we’d be able to make it an easier project.

The young man who had done a three minute piece for me for the CFDA Awards was Frédéric Tcheng and I would call him every so often after I made that relationship with him and would talk to him about my film, and my problems and blah, blah, blah. At one point he wound up being the one to say to me “after I finish this project”—he was working on the Halston film at the time—he said, “I want to be able to do your film, but only if you will agree to co-direct it with me,” because he didn’t want it to be a film about someone that was already living and living such a life that was so full that he wanted me to be responsible for telling the story with him.

That’s how it came to be.

That leads me right to my next question. Frédéric has obviously made some really great documentaries that are centered around the fashion industry, well aspects of it, like Dior and I, and Halston, and now, of course, Invisible Beauty.

Now knowing the context that you guys had already had a preexisting relationship, and these were the conditions under which he would have done the film, how was it collaborating with him, and also being the director and subject of the film?

It was great. You know why? Because Frédéric is a really wonderful human being. He’s talented and I always give extra credit to people who are engineers, and then they go into another field. Because these are just unique human beings. They don’t see things the same way, or they read things differently, they just have a brain that just works a little differently.

I agree.

Virgil Abloh is a perfect example of something like that. They’re coming off a different spin. He also is talented, and so he made things much easier because he was getting to know me and he became [the] audience. He was curious. He’s not a fashion person. He’s just wound up making these fashion documentaries, but he’s not that at all. So he was the student of watching Bethann tell her story. We got along, too. We had this deal that if we ever basically didn’t agree with something, and this is how we started out before we even got into making the film, that we would have to talk each other through it until we convinced the other. But we never came into that place where there was anything that I didn’t want to do, or he didn’t want to have, so it always worked out.

Being the subject, I just had to stay out of my own way, let things be, trust him, because I did trust him and I loved his projects prior. I liked him as a person already. I trusted him so there were times I noticed I would tell him things that I normally wouldn’t tell somebody who was so new in my life. That’s how some of the stuff came up about Kadeem [Bethann’s son] because that was just happenstance. He just so happened to be in the car at the time that I was talking about it. The guy always has a recorder on, he’s always ready to go, so you never know. Luckily, I believe in telling a good story. So I didn’t want to start to edit to the point where you just blow it.

I think in general, one of the throughlines that I really also loved about the film was not just you as a mother to Kadeem, just that you are mother. When I use the term mother I mean in the industry, and to a lot of people coming up in the industry, you’ve always had that role. And it was interesting to see the juxtaposition of you as a mother to your son and to so many, so many other people. You see it in the way that you communicate and the way that you even approach advocacy. You said something in the documentary to the effect of not only trying to help Black people, but also trying to educate white people, and that to me was a mothering approach to how you look at things. I would like to know how motherhood and how being that figure has shaped your approach to advocacy.

Good for you that you could align it that way, because that is a good way of looking at it. It is a very maternal way of looking at something or approaching something. … It’s a very interesting thing that you know you can do that and the approach is like you’re educating someone. You believe in your heart that you’re educating them because you could see that if they only saw what they were doing, and they could see how it looks, they wouldn’t do it. The industry that I’m in, the modeling industry and the clothing/apparel industry which is the fashion industry, they wouldn’t want to be known or to be thought of as a racist. That’s not their intention. It’s important that you can help them to see. If you don’t tell them, how the hell are they going to know? And if you don’t show them the way that it appears, that would make them much more self conscious about it because that was truly not their intent. Sometimes you could just leave things alone and walk away from it.

But then, you know, some people just call to do things. I think in my case, I’m just called to do the things that I’ve done.

You did an episode of the Cutting Room Floor podcast in 2020 with Recho Omondi and I loved that episode. You mentioned in that interview that after the Civil Rights movement, there was more inclusion of Black people and we’ve watched it go away, specifically as it pertains to Black models on the runway or in advertising. Like, we saw what was possible from designers like Steven Burroughs, Halston, and Willi Smith, who had Black models on the runways, and we can feel the void when it is missing.

After 2020, there were a lot of initiatives and promises to bring more diversity to the runway and fashion industry as a whole. I am curious to know where you think we are now compared to where we were then.

Where we are now compared to the ’70s, ’80s?

Yes.

It was something that happened in the mid ’90s and I use the Berlin Wall coming down as a good example of how that opened up the possibilities for model scouts to go into those regions in Eastern Europe, and discover those girls and give those girls an opportunity to come to America and be seen by casting directors and stylists, which we never had before in the industry of fashion. The only thing we had as casting directors and stylists were for catalogs and commercials in advertising, not in the world of fashion, per se. So that happened and that changed everything because all of a sudden we had this industry changing. It was a new discovery; which happens! That’s what makes everybody get excited about things. It wasn’t like we hadn’t already had girls of color walking the runways, being in fashion, being there all along. We existed before and now it was changing again.

Now, of course, when it comes down to the model of color, I think she, he [has been] there for a while. Because that’s not what’s going to change so much, like the corporations are changing. Yes, after the Black Lives Matter movement, that really kicked things into high gear and that made a lot of people feel a little self-conscious. This movement was an integrated movement. So this became something that made people look at this as not just a Black thing. Because of it, it encouraged a lot of people to get into the business, to do things, to work, to participate in bringing their desire to be in an industry that is very narrow and tough, which is the industry of manufacturing. Retailers [are] and other people saying, “Come along, we’ll help you,” and I’m telling the group I work with, the designers, “Be thoughtful. Everything that shines is not necessarily gold.”

So now it’s turning around again; I hear from many that the assistance, the money, the opportunity, they’re drying up. In big corporations, DEI executives are now being replaced or those jobs are going away. Everything rolls right back down to money. You know, if you are succeeding at something, then people will continue to work with you and you’re helping them to be successful. But if it isn’t, and that means that they’ve got to keep putting it out, eventually they’re going to stop. It’s still the same old industry. And I’m not mad, you know, I’m just saying that we have to be wiser about what we can anticipate. You have to be so exceptionally good at what you do that they will keep lending because they can see the return. And the return is always a sale or a dollar. And that’s not to look at anybody strange because we do live in America and that’s what this country’s built on.

You mentioned that when you started Bethann Management that it was scary, and at the end of the day it wasn’t what you wanted to do, but it was what you were called to do. Do you feel like this documentary falls under that same category for that same reason? Is that how you felt when you were doing this?

Yeah. I mean, you don’t think you have something to even make a film about. You really don’t. You don’t know it until you see it. Then when you see it, you say, “Well, OK, what do I know?” [laughs] You just give the guy [Frédéric] credit, you say, “Well, you’re right.” I just want to make sure I did my part. I think it was another call to duty. I think writing the book is the same thing. People have been saying it to me for over 30 years, “You’ve got to write a book. You’ve got to write a book.” OK. So you get a book deal, and then you’ve got to write the book. The film is different because I decided to make the film about me just maybe five years ago. Then we made the film in three years. It comes down to the fact that you have a sense of responsibility for certain things and there are people out there who really believe that you owe your story told and people wanna know and people are inspired by the things that you’ve done in the past.

Is there anything that was left on the cutting room floor that you wish made it into the documentary?

Oh, he had seven hours of things he loved. Then he had to get it down to four hours to show it to me. All we could think about watching the four hours, because the four hours is what made me believe it. Then all of a sudden I said, “Well, I guess I do have a story.” Then I thought, can we make this a series? We got very excited, myself and Frédéric, and our producer was like, “Get over it. It’s a feature film, do just get that out of your head.”

Last question. When is the book coming out?

Yeah, that should have been your first question! In every Q&A, someone asks that question. It doesn’t escape. They’re hoping that I finish and deliver the rest of the book by the end of this year. I’m hoping that they can have the book out by the end of 2024.

I do have another bonus question. Is it a lot—on top of what you’ve already done, what you’re continuing to accomplish—for people to just, myself included, ask when’s the next thing coming? Or do you feel that’s just part of your calling to continue to create and make these things for us that educate us?

Hmm. Interesting.

As soon as I asked you that, I was like, damn, the documentary is coming out and I’m asking where’s the book?

Yeah, no, everybody asks where’s the book. Because the documentary seems to have made people want to know about the book. When we were first starting this, I was already starting the film, but then I got the book deal. And then we [the publisher] were thinking to get the book out first, because usually back in the day if people saw a film, they wouldn’t go pick up the book. The book can maybe drive people to see a film but usually not the other way around. But then eventually when they saw a little bit of the film, they saw one thing didn’t have to do with the other because it’s so different. It’s just the same person. So I think that many people really have great interest in it because watching the film and seeing that part of the storyline was the writing of the book makes everyone watching this film think, I gotta read that book now. I said, “Well, it’s not that juicy!” [laughs] They feel that this one will almost encourage the other, which is also very good.

For me, I’m doing exactly what you said earlier. I’m doing what I’m responsible to do. And I think writing the book, of course, yes, I got to do that. Doing this film, yes, I had to do that. And, you know, now those things are done. And what would I do going forward? I hope that I can, you know, build a foundation of something that keeps young people that go into business educated about business.

Invisible Beauty is now playing in theaters in New York. It expands to Los Angeles on September 22 and additional theaters on September 29.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Marquia Walton is a writer and digital producer based in Bedstuy, Brooklyn. Further interests, in no particular order, include: cooking, natural wine, racial justice, sustainable food systems, universal healthcare and telling it like it is.