One night in November, when I was 13 years old, my parents took the train to New York City to celebrate their wedding anniversary. They took in a show, went out to dinner, and had the last fully carefree experience of their lives together. When they returned from the trip, my mother was sick. They blamed her virus on a “very crowded train,” but in actuality, my mother was actually beginning to show signs of a much more serious illness—we just didn’t know it at the time.

In fact, it would take years before doctors finally discovered the true cause of my mother’s near-constant aches and pains. Pains that caused her to leave her job, pains that disabled her and often confined her to a bed, a wheelchair, or, on the really, really bad days, a hospital room. Pains that altered my childhood, the state of my family, and her ability to mother in the way she wanted, and the way we had come to expect. We would eventually learn that what seemed like a bad flu or virus caught on a train to NYC was actually multiple sclerosis. She was 37.

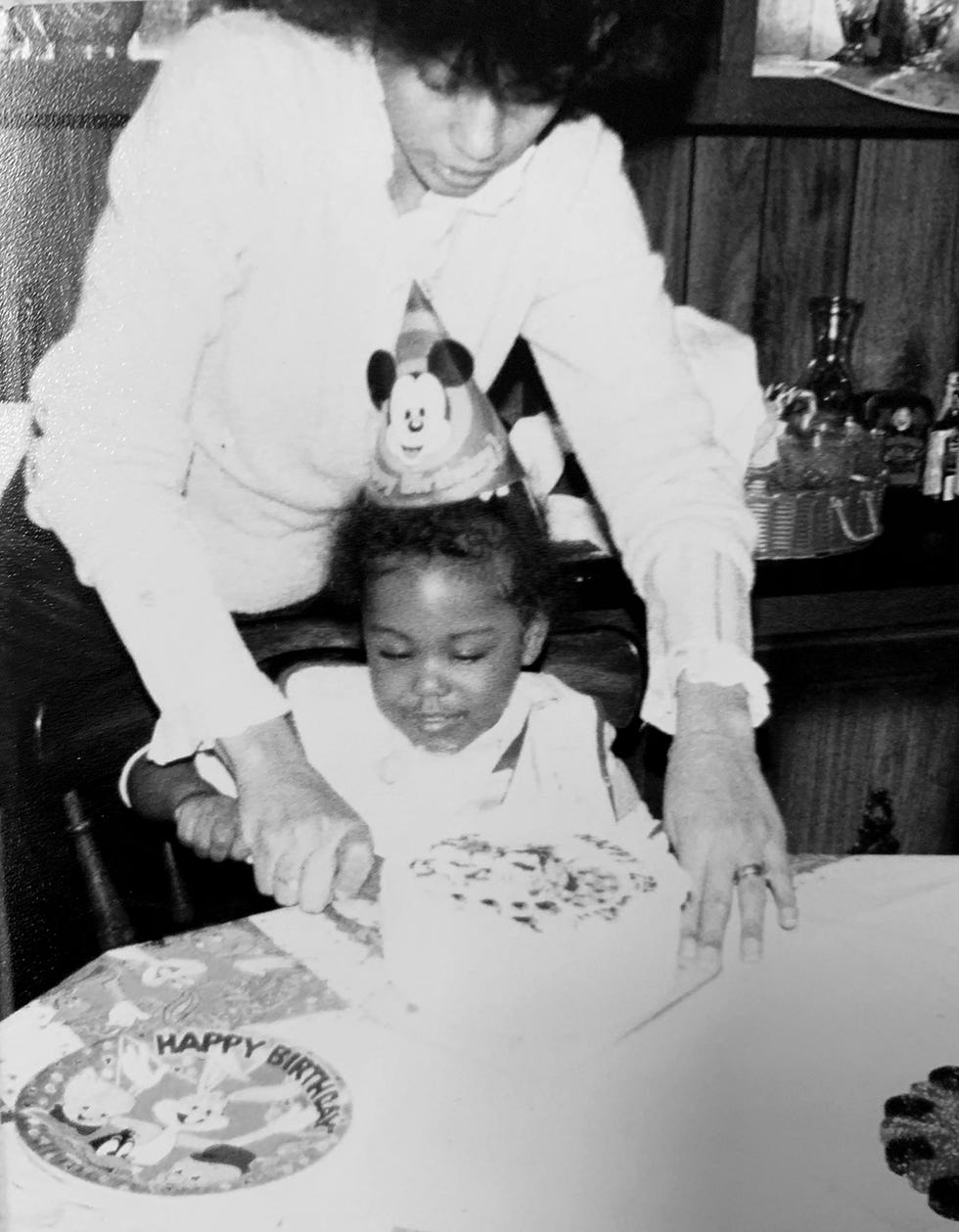

As a family, we did our collective best to keep it together, and my mother did her best to keep our life as normal as possible, MS be damned. We threw great parties, Christmas was always a raucous get-together, and my mom somehow miraculously maintained her role as an active and involved parent and the leader of our little family. No matter her physical or emotional pain, she was still in charge, and made that fact abundantly clear. We muddled through and didn’t talk about it much, but we made our new life work for us.

Nearly a decade later, long after her condition stabilized, the intense aches and pains returned, once again with no known cause. We’d been down this road before, so we all committed to being more aggressive with our health care providers, and this time we had answers in months instead of years: breast cancer, stage 4. The disease had camped out in her bones and was always “treatable, not curable.” True to form, she once again fought hard to take care of our family and maintain the best and most joyful life possible in the midst of nearly three years of anticipatory grief. Then, on an otherwise unremarkable day in February after sharing a joke, she collapsed in my arms and was dead a few hours later. She had just turned 49.

A few days ago I turned 40, and officially entered the decade in which my mother passed away. I am filled with grief and anxiety. I’ve struggled to put my finger on what exactly has me so worked up. My mother has been gone for nearly 15 years, nothing about living with loss is new, and I even wrote a book on grief, so it seems like it should be easier to figure out what is upsetting me about my forties. I’ve come to realize it’s everything.

This decade I’m embarking on is forcing me to consider how much I didn’t actually get to know my mother. As a mother now myself, I see how much of our relationship with our children is centered around them and their individual and specific needs, not around who you are as an individual, independent of motherhood. My son is still young, and as he grows older, I fully intend to ensure he knows as much of me as possible, as a full human, but that learning comes naturally in stages as he grows and develops.

When my mom was dying, and I was in my twenties, I tried to come up with a strategy to ensure I could capture all the answered questions I might wish for some day. I drafted a list of queries I called “intangibles” and got through as many of them as possible. “How do you know when someone is The One?” “What should I look for in a spouse?” “What does it take to be a good mother?” Fifteen years later, when I look through my notes, most questions never answered because of how quickly she died, I realize a critical error. I thought I could capture the most important questions in life in that brief moment of time before her passing when I was only 25 and knew very little about life, when in actuality we don’t even know what questions we are going to need answers until we live them.

At 25, I didn’t know how my life would shift and change, or how I would shift and change after her absence. I know more change is coming, and I grieve not having her here to share the more “adult” parts of her life with me, and weigh in on mine. That’s the thing about knowing and sharing and learning with someone else: it comes in stages, not all at once. So as close as I considered myself to be with my mother, the older I get and the more life I experience, the more clearly I can see all that’s been missed.

Now that I’m officially a real grown-up (a 40-year-old with a husband, a dog, a mortgage, a child, and a business to run), I am being forced to reckon not so much with my own mortality, but with the limits of knowing and the limitlessness of grief. How much do we really know about the ones we love? Particularly the ones we love who care for us? While I may have been one of my mother’s caretakers, she never stopped being my mother. She always offered advice, counsel, and comfort whenever needed, despite her own physical or emotional pain. I don’t know how hard it was for her to be sick. I don’t know what it was like for her to be a disabled parent. I know what I witnessed, but I can’t grasp the toll her illnesses took on her marriage to my father, or anyone else in her life.

As I grow older and life’s challenges seem to grow larger and more insurmountable, I grieve not having her here to guide me. I want her to show me how to be a great mom. I want her to advise me on how to support my husband as he prepares to lose his own mother. I want her here for all the joy I know this new decade will contain. Because I don’t have those things, and perhaps you don’t either, I am leaning in on the knowledge that I do have. I know she loved big and deep, and I seek to do the same. I know her commitment to kindness, compassion, and generosity was real, and I will continue to let those values guide me as these next 10 years unfold. I may not know just how hard things really were for her, but I know that when things got hard, she relied on faith, friends, and a little retail therapy, too. And while I know I missed out on a lot, namely a real adult relationship with my mother, I also know I will always have her love. Perhaps that’s all I really need.