The Justice Department announced on Tuesday that it has reached a historic civil settlement with more than 100 survivors over allegations that the FBI failed to properly investigate claims about former USA Gymnastics doctor Larry Nassar, who abused hundreds of young girls under the guise of medical treatment and is now serving a life sentence in state prison. According to a press release from the DOJ, the $138.7 million settlement resolves 139 claims.

Olympic gymnasts Simone Biles, Aly Raisman, and McKayla Maroney are among those who held the federal authorities accountable.

Though Biles and Raisman have both been vocal about Nassar, Maroney is less outspoken about what she endured. However, in a rare interview with ELLE from 2021, the gymnast opened up for the first time about being molested by the pedophile doctor. “We would be like, ‘No, don’t do that. We just want you to work on our backs, our shins, our feet,” Maroney said. “And we’d be annoyed. We’d be mad. We all hated it.” Raisman, who spoke with ELLE for the story, said she and Maroney were abused “at the same location, same day,” and that they “helped each other survive.”

Below, ELLE’s profile of Maroney from October 2021. Trigger warning: This story contains graphic depictions of abuse, addiction, and mental health struggles.

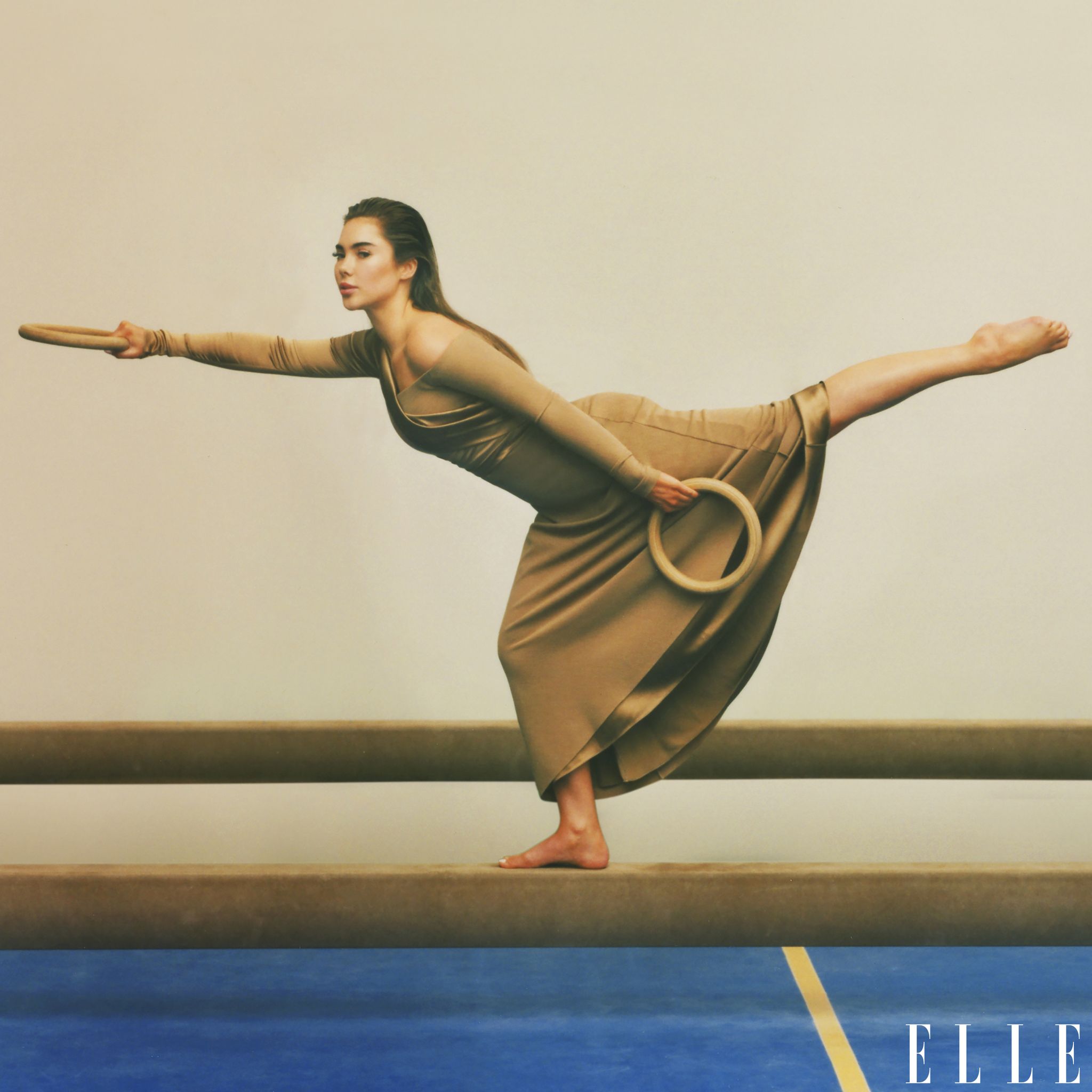

An all-out sprint, a leap of faith, and a series of disorienting turns. Land gracefully, and you’ve just described the perfect vault. In the case of McKayla Maroney, you could just as well be talking about the last decade of her life.

Back at the 2012 London Olympics, the gymnast stuck the landing on a two-and-a-half twisting Amanar vault, one of the most impressive feats in the sport at the time. You may not remember. But you definitely remember her face on the second-place podium after landing on her butt during the individual vault finals. Pursed lips sagging slightly to the right, and dagger eyes—the same so-over-this scowl of someone in line at the DMV. The “McKayla Maroney Is Not Impressed” meme was born. Overnight, Maroney’s face was Photoshopped next to everything from Beyoncé’s baby bump to the Great Sphinx of Giza

When she abruptly announced her retirement three and a half years later, not even those closest to her understood why she would give up a shot at redemption—at individual gold. But behind the scenes, Maroney had been launched headfirst into the most challenging chapter of her life, one that threw her twice as many twists as an Amanar.

After the Olympics, Maroney fought back against hackers who had posted her underage nudes online, battled a debilitating eating disorder, grieved her father’s accidental death—and bravely helped the FBI take down one of the most notorious serial predators of all time. “Clearly I’ve been through a lot,” Maroney says. Since then, she has been doing a lot of work on herself to get back to a good place. “The spark is back—and everybody’s noticing,” she says.

This summer, Maroney invited me to her blink-and-you’ll-miss-it apartment in Southern California. She moved in last year after living at her mom’s house for a while, and says the place has been a fresh start. Inside the sunny two-bedroom, there’s an onyx obelisk atop a neat stack of meditation guides on the coffee table. Dusty-rose-colored curtains match a yoga mat left on the floor. Above the TV in front of us is a swirly piece of abstract art that Maroney painted during what she calls her “dark” years.

At age 25, Maroney has already survived more than anyone should have to endure in a lifetime. Before the interview, I found myself wondering if she would be closed off, guarded—as she has every right to be. But here in her safe space, amid calming crystals and cozy colors, she welcomes me with open arms and a carton of peanut butter cups. As we snack, Maroney tells me that watching Simone Biles at the recent Olympic trials inspired her to dig up the video of her own Olympic vault from nine years ago. “Catwoman energy,” she recalls with a grin.

As the story goes, Maroney owes her career to a different animal: the gorillas in Tarzan, which she imitated as a toddler by hopping around on her hands and knees. Her mom, Erin, enrolled them in Mommy and Me classes at a gym in Orange County, where they lived when Maroney was 18 months old. By the time she was eight, she was training in the gym for eight hours a day. Her fifth grade yearbook quote proudly stated: “I want to be in the Olympics!”

Maroney was the kind of kid who possessed the preternatural drive to make that happen. “My mom was really good at letting her kids make their own decisions,” she says. “Looking back at it now, I wouldn’t have been who I was without my mom letting me be independent.” She studied footage of her hero, 2004 Olympic champion Carly Patterson, and ran through routines in her head. “I was a little OCD,” Maroney admits. At 14, she was being coached by two former elite gymnasts from Russia and Bulgaria. After delivering a near-faultless vault at the 2012 Olympic trials, she was selected to represent Team USA in London alongside Gabby Douglas, Jordyn Wieber, Aly Raisman, and Kyla Ross. Maroney came up with the nickname for the tight-knit group: “the Fierce Five.”

Athletes who are favored to win gold, but don’t, react in different ways. Some melt into tears; others put on a brave face. After falling on her back-side during the second of her two final vaults in the individual competition, Maroney was visibly pissed. Ross says she and Wieber accompanied her to the Olympic Village cafeteria for a conciliatory McDonald’s vanilla soft serve cone. “We were almost a little bit nervous to see her after she was up on the podium, because we all really felt bad for her,” Ross says. “We knew she was not making that face at all to be funny.”

But the silver medal did have a silver lining: Maroney became an instant meme. Her younger brother, Kav Maroney, calls it, “a blessing in disguise that maybe we didn’t realize at the time—because for us it was the face of getting second.” When the Fierce Five stopped by the White House after the Games, Maroney posed with President Barack Obama to make her “unimpressed” face. She landed a sponsorship deal with Adidas, and debuted her own line of leotards. “McKayla became something completely different than if everything had gone according to plan and she ended up winning,” Kav says.

Going viral was fun, but it wasn’t gold. “My mom and dad were never like, ‘McKayla, you have to be perfect,’ I put those expectations on myself,” Maroney says. “I think that obsessiveness is what it takes.” By 2013, she was training for a second shot at the Olympics and had placed first on vault and third on floor at the Secret U.S. Classic. That same year, Maroney was one of four gymnasts to represent the U.S. at the World Championships in Belgium, where she won a gold medal on vault. All signs pointed to her being an Olympian once again in 2016.

But after the competition, Maroney says her body felt “completely broken.” She suffered an avulsion fracture in her knee, and was forced to take time off. “Having to process that you could be done is the hardest thing for an athlete to go through,” Maroney says. “It’s your identity.” Ultimately, though, it wasn’t that injury that forced her out of the sport.

In 2014, Maroney learned that nude photos she took as a minor were part of “Celebgate,” the scandal in which nearly 500 pictures of celebrities were stolen and posted online by hackers. “I was so ashamed, like, ‘Holy shit, even my aunt is seeing that now.’ It was so fucked up,” Maroney says of the photos that circulated so widely even some of her dad’s coworkers knew about them. In the conservative world of gymnastics—little girls in pretty boxes—Maroney wasn’t treated with empathy. Mothers of fellow gymnasts told their daughters to steer clear of her at the gym. “When you go to the Olympics, people see you as a little girl and that’s all they want to see you as. Anything else is vile to them. It’s like, ‘How could you? You’re a role model,’ ” Maroney says. “I was no longer respected.” For her Olympic teammate Ross, who trained at the same California gym growing up, it was shocking to learn how fast the sport could turn its back on one of its best. “If that happened to me, I definitely would have been scared to come back,” Ross says.

Maroney packed up her leotards at the age of 20 and shoved them deep in the back of her closet. When her mom asked why she was retiring, Maroney said she didn’t want to talk about it. It wasn’t the only thing Maroney was keeping from her mom. In the summer of 2015, she had answered a call from the FBI. They wanted to know about Larry Nassar.

By the time Maroney made it to the national team in 2010, USA Gymnastics and the wholesome appeal of its female athletes had become a bonafide financial powerhouse run by businessmen. The actual gymnastics stuff they left to former national team coordinators Bela and Martha Karolyi, who operated the “Karolyi Ranch,” a now notorious and defunct training facility outside of Houston. The young women widely considered to be among the best athletes in the world slept in bunk beds sometimes crawling with bugs, and the bathrooms were dirty. “We were not treated like Olympians, we were treated like we were in a military camp,” Maroney says.

None of the adults seemed to care about her well-being beyond what it took to help her win. “It was a perfect breeding ground for Larry Nassar to sneak in,” Maroney says of the longtime national team doctor. “Our coaches were so focused on us being skinny and us being the best to get the gold medal for their own ego.”

Maroney was molested by the pedophile doctor during one of her first training camps. After, “he was like, ‘You know, to be a great athlete, we sometimes have to do things that other people wouldn’t do,’ ” she says. “Basically, he was silencing me and saying, ‘This is what it takes to be great.’ ” Her future Olympic teammate Raisman, who was also molested by Nassar, says they were too young to fully understand what was happening—but they knew that it wasn’t right. “We were being abused at the same location, same day,” Raisman says.“We helped each other survive.”

Maroney remembers tightening her legs, begging Nassar to work on any other part of her body. “We would be like, ‘No, don’t do that. We just want you to work on our backs, our shins, our feet,” she says. “And we’d be annoyed. We’d be mad. We all hated it.” The teammates discussed the abuse in uncertain terms. “We all talked about it in little ways,” Maroney says.“We never said, ‘We’re being molested,’ but we would say, ‘It’s like we’re being fingered.’ We’d even say it was time to go get fingered by Larry. But we were 13 and didn’t even know what being fingered was at the time. We were really young and naive from living in a gym.”

When the FBI reached out, Maroney felt like someone was finally listening. In her first two-hour phone interview with them, she says she relayed in intimate detail how Nassar had sexually abused her for years. As Maroney patiently waited for something—anything—to happen, the abuse continued. A damning inspector general’s report from the Justice Department, released on the eve of the Tokyo Olympics this July, concluded that FBI officials failed to respond to the allegations “with the utmost seriousness and urgency that [they] de-served and required” and “made numerous and fundamental errors when they did respond.” Between the summer of 2015, when Maroney first talked to the FBI, and September 2016, when an Indianapolis Star exposé spurred a renewed energy into the bureau’s inquiry, at least 70 female athletes were molested by Nassar, who has pleaded guilty to multiple charges and is now serving a de facto life sentence of up to 175 years in prison for sexual abuse. The FBI said in a response to the report that it “will never lose sight of the harm that Nassar’s abuse caused,” and is now taking “all necessary steps to ensure that the failures of the employees outlined in the report do not happen again.”

It’s a move in the right direction, but “it wasn’t a case of one bad apple,” Maroney says. “Things are changing, but this was a systemic problem.”

Fed up with the plodding pace of the FBI investigation, in October 2017, Maroney broke her NDA with USA Gymnastics, which “was forced”on her, according to a lawsuit she filed against the U.S. Olympic Committee, USA Gymnastics, Larry Nassar, and Michigan State University. Maroney was the first of the Fierce Five to bravely go public with her story, writing on Twitter: “I was molested by Dr. Larry Nassar… Our silence has given the wrong people power for too long, and it’s time to take our power back.”

In January 2018, more than one hundred women, including Maroney’s Olympic teammates Raisman and Wieber, gave victim impact statements at Nassar’s sentencing hearing in Michigan. Maroney’s own statement accused Nassar of molesting her both at the 2012 Olympics and in a Tokyo hotel room one year earlier for so long that, she says now, he “blacked out—kind of like he forgot how long he was doing it, because the whole time he’s pleasuring himself, he’s enjoying it.” She was 15, naked, alone, bawling, and “looking around for a knife,” she says, “because I thought he was going to kill me that night. I was like, There’s no way he is going to let me go after what he just did to me. What’s stopping me from saying he did this to me? But then he was like, ‘Okay, you can go to bed.’” Maroney says she woke up the next morning and wanted to tell someone, but was “surrounded by intimidating coaches and didn’t have my mom with me.” “I felt completely unsafe,” she says. “And that was the first time I was like, ‘That was abuse.’ ”

Maroney didn’t attend the hearing in person—she says she was tired of having to relive her trauma “over and over and over”—but her statement was read aloud for her as she sat at home trying to forget about the abuse. “To have people say I can’t move forward with my life, because I have to do all this stuff first, was really hard for me,” she says. “I just wanted to become someone else.”

Survivors know speaking out can come at a cost. As Maroney began to feel like she was losing her grip on the way the world saw her, she fixated on other ways to control her life. “I already had that obsessive control thing, so it just switched from gymnastics to food,” Maroney says. She tried a slew of dangerous fad diets and starved herself for three days in a row. “I forgot I had ever even been successful at gymnastics, because I went from being great to feeling like, ‘Oh my God, I’m ugly, I’m gaining weight, I’m suffering with food, and I just went through all this abuse,’ ” she says. At home, her brother Kav watched as she withdrew further and further into herself. “She never got to appreciate what she accomplished because she was going through all this stuff as a result of it,” he says.

By the end of 2017, Maroney stopped posting on Instagram and all but disappeared from the public eye. She resurfaced two years later with a sunlit selfie from the car and a cryptic caption: “Last few years, a lot’s happened.”

For so long, Maroney felt betrayed and undermined by the traditional institutions that were supposed to protect her when she needed them most. One day, her chiropractor offered up an intriguing new possible salvation.“Do you believe in angels?” she asked Maroney. On her chiropractor’s recommendation, Maroney sought help from a mysterious new group called the Church of the Master Angels, a self-described “unitary, non-denominational, faith-based community Church” with a chapel located deep within the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina. There, some followers of CMA meditate near a 14,680-pound crystal and pay up to $10,000 for elite four-day-long workshops. The Church is led by a man Maroney calls “Master John.”

At her first event in 2016, Maroney says Master John, whom she describes as a spiritual Tony Robbins, helped her feel “immediate” relief from the emotional toll of the last year. She says she went back twice in 2018, and that her mom has been to an event, too. “It’s obviously not for everyone,” Maroney says.“If you want to go to a healer, go to a healer. If you like psychics, whatever, do that. At the end of the day, it’s my choice.”

When The Daily Beast published an article in February 2021 pointing out that some Master John followers believe he can heal illnesses like HIV and cancer, Maroney found herself on the defensive. “All my friends were like, ‘Wait, this is so crazy. You’re in a cult?’” Maroney says. “I’ve always believed in God and more than just myself. But I’m not religious; I am not in a cult. None of it is true. The article just attacked me over a necklace that I had been wearing. I do meditation and pray, but there’s nothing weird that I do.” She says she hasn’t been to a Master John workshop since the start of the pandemic, though still wears the necklace in question, which she bought on the CMA website, as a security blanket.

Maroney leans across the couch to show me the geometric pendant she’s wearing, which looks like a tiny silver dream catcher. It’s a form of protection against evil, she explains, similar to a Kabbalah bracelet. “There are dark people and darker energies that see you and don’t wish you well,” she whispers to me. “I like to feel like I’m protected in some way.”

By 2019, Maroney was finally starting to feel at peace with herself. She had enrolled in an online course for people with eating disorders, and tapped into meditation to cope with burnout. Then, in mid-January, her dad Mike suddenly died as the result of an addiction to pain pills he had been keeping secret for years. Maroney knows a thing or two about locking up pain; she didn’t tell her parents about Nassar until after the FBI started looking into him. She says finding out about the abuse took a toll on her dad. “I think he probably self-medicated with opioids, Xanax—things like that,” Maroney says. “And we didn’t know because he felt like the attention shouldn’t be on him.”

The day Mike revealed his addiction was also the last day Maroney saw him alive. He had committed to getting clean and made plans with a friend to detox at a hotel without medical supervision. The last thing Mike told her before leaving was that he wanted to make things right. Maroney assured him that she held no judgment. “You’ve seen me go through so much,” she told him. Several days later, Mike had a heart attack and died as a result of the detox.

Maroney says the grief was like “an ocean of sadness that I couldn’t get out of.” She reverted back to her old coping mechanisms, starving herself for 10 days in order to be “skinny enough” for the funeral. But after a decade mired in secret suffering, Maroney and her family knew that this time they needed to come together. “It’s not that we fell out of touch as a family,” Kav says. “It was just like everybody was doing their own thing…. We had no choice but to be together. We spoke up.”

As Maroney learned to share more with her loved ones, she began writing everything down. Her words turned into song lyrics. After all her years of struggling, music, in the most literal sense, helped her reclaim her voice. In typical Maroney fashion, she gave it her all, enrolling in vocal lessons and teaching herself how to use recording software. When L.A. producer Maxwell Flohr first heard her demo at an Echo Park studio in October 2019, he was struck by how she “used music as a coping mechanism.” Since then, they have produced 25 songs together, many based on Maroney’s writings—three of which are on Spotify.

At her apartment, Maroney sings one for me, an unreleased ballad called “Motivation.” She wrote it during the first Christmas without her dad. “People were putting up Christmas lights, and I literally had no motivation to even get out of bed or to sing or to do anything that was going to benefit me in the long run,” she says. “Deep down, I know I wanted so much more.” Her soprano voice is soft and sweet as she sings about rediscovering a sense of purpose. “I’m not, like, Ariana Grande,” she says sheepishly. “But I do have a little bit of a gift with songwriting.”

Maroney’s strength was put to the test yet again in January 2021, when doctors discovered she had kidney stones and needed surgery. The thought of taking pain pills worried her; she resolved not to hide behind the unhealthy coping habits of her past. She passed on strong painkillers, and opened up to the world about her recovery, writing on her new wellness Instagram account Glohe (pronounced “glow-y”) that she was “through the worst of it, and in the light.” The account has become like a safe-space for Maroney, who posts lengthy captions about overcoming her eating disorder, how to practice self care, and her new health and beauty routines.

For the first time in a long time, Maroney is firmly in charge again—and using her own experiences to help others. She’s developing several projects, including a memoir and the McKayla Collection on NFT marketplace OpenSea, where her “Not Impressed” meme (along with several original art pieces) was up for auction. She is also using the large following she started amassing with that famous grimace—nearly a decade ago now—to help others affected by abuse. “I want to be looked at as someone who just keeps going, because that’s what we have to do in this life,” Maroney says. “For so long, I was surviving. Now I feel I’m actually living.”

That includes making up for lost time with friends who have been there through it all. After our interview, Maroney has a sleepover date planned with Raisman, who is in town from Boston. “When we get together, I feel like a teenager again in the best way,” Raisman says. Tonight, there will be no talk of the bad times—it’s a totally gymnastics-free girl’s night in. Only food delivery, rom-coms, and “girl talk,” which is really just code for “talking about boys,” Maroney says with a grin. “And we can talk about that for hours.”

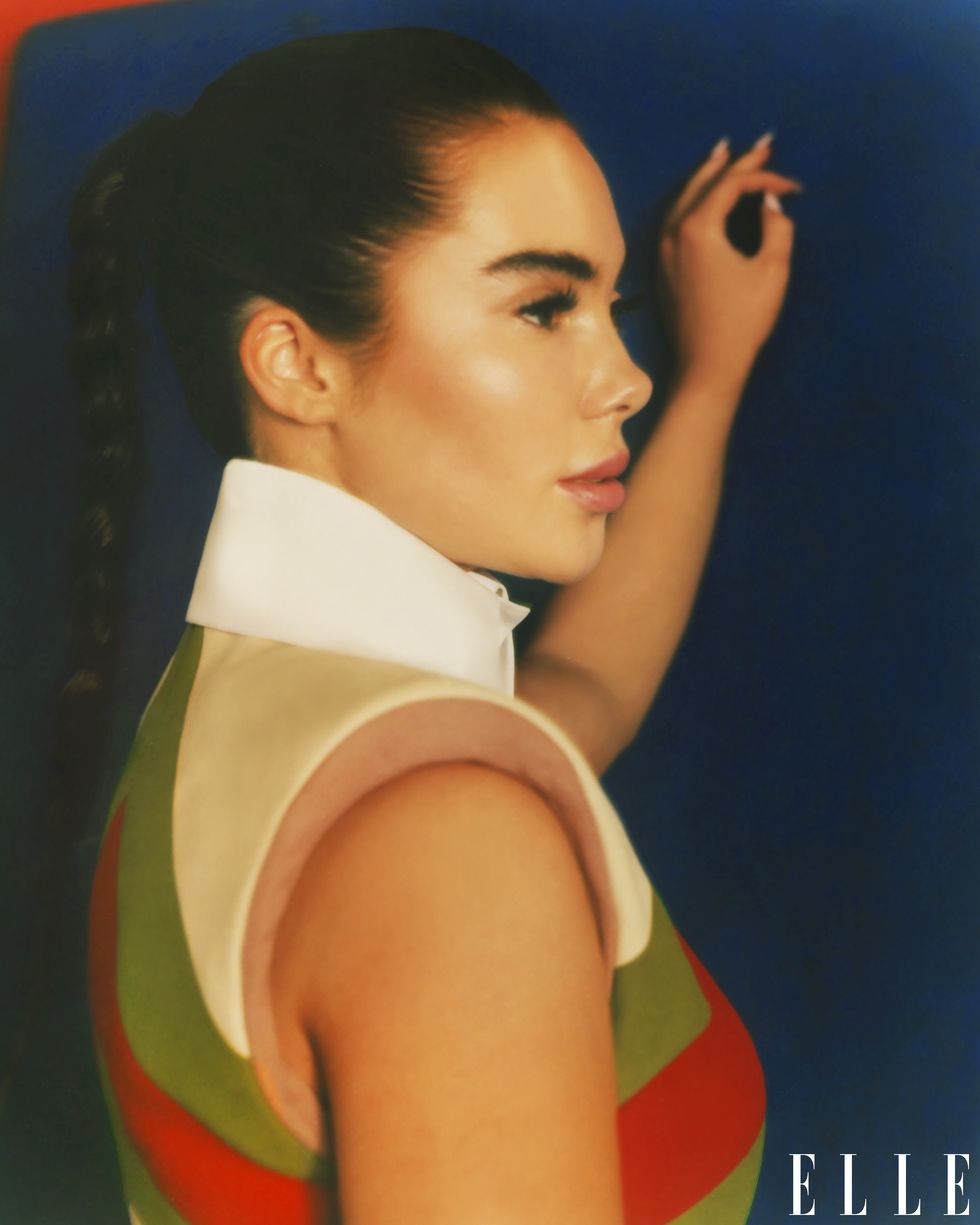

Photography: Taylor Rainbolt; Styled by: Ashley Furnival; Hair: Christian Marc for UNITE; Makeup: Stephanie De Anda; Producer / Visual editor: Sameet Sharma; Special thanks to American Gymnastics Academy.

This story appears in the October 2021 issue.